Mind embodied in beautiful sounds, or Music in the context of neuroscience

In its quest to penetrate into the mysteries of sounds, humanity has certainly succeeded. Still, music is a subtle substance: the deeper you delve, the more mysteries appear. Melody or mind – what is the primary influence? People create new instruments, rhythms and directions, but can we say that music changes us? Is genius a gift from above or can anyone become a Mozart? Neuroscience sheds light on the nature of musical creativity.

Nobel Prize winners in physiology and medicine in 2014, John O’Keefe and the spouses Mei-Britt and Edward Moser were given this prestigious award for the discovery of the brain positioning system. Scientists have confirmed the hypothesis of Kant! It turns out that in the process of cognition of our world, the spatial cells of the brain (neurons), dotted in the head, are something like a GPS scheme. An animal with a head or a person – it does not matter, as a lost horse or a drunken reveller on autopilot will reach home with equal success. The internal navigator accurately remembers the routes and determines the distances.

You ask, “what does music have to do with it”? The fact is that there is another map marked with active neural blocks (modules) responsible for the musical abilities of a person. Those who have seriously engaged in music or at least joined it in a tangent have zones of activity that are clearly expressed and this cannot be said about people who completely bypassed this area.

Beautiful – in the head

The feeling of beauty does not appear from scratch. It is created on a global level in the process of evolution. It is known that only humans can understand beauty from all beings inhabiting the Earth. Each of us receives this gift at birth, developing and passing it on to the next generation.

elegant nice piano blues or jazz background

What is the connection between the creative principle and the physiology of the brain? This issue is concerned with neuro-aesthetics. The key idea belongs to the British theorist-neurobiologist Semir Zaki. It is simply that, in the pairing of “aesthetic experience & the brain”, the latter is the leader.

What happens in our convolutions when we listen to Bach? What is the secret of absolute hearing? Why do some people reach towards symphonic classics and others – guitar distortion and extreme vocals? In search of answers to such questions, American psychologist Peter Janata, in the early 90s, founded another scientific direction: Cognitive neurobiology of music, a sister of neuro-aesthetics, which is immersed in the depths of grey matter, armed with diagnostic equipment. Her current devotees are the head of the European community of cognitive musicology, Iren Delij, former musician, now writer and professor at McGill University, Daniel Levitin, researcher in the field of neural-coding of speech, Nina Kraus, author of techniques for hearing music research, Carol L. Krumhansl and American neurologist and neuropsychologist, Oliver Wolf Sachs. These people and their like-minded supporters go forward by experiment, discovering new laws of beauty.

Let me sing to you

The kid is only two years old. No one taught him music, but he perfectly senses the difference between melody and speech and sings, as if falling into notes. Dad picks it up and the song is familiar to him, but, at the same time, it is mercilessly different.

Why is this happening? Age, here, has nothing to do with it and the auditory system of musical people and those who lack in this quality is the same. It is all about the internal information comparison module, thanks to which false notes cut sharply, as the brain compares the melody with the ideal scale. When trying to assess the quality of sound, average people include brain areas responsible for memory and absolute hearing owners are not required to compare it with the standard. They are able to feel falsely intuitive. A musical ear can be developed and there are special techniques known to any music teacher. Why are great composers unique?

“Music is the unconscious exercise of the soul in arithmetic” (V. Leibniz, German mathematician)

Genius God awards ‘architectonic’ hearing. The mathematical term, applied to music, was first used by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and the composer and musicologist Boris Asafiev called ‘architectonic’ hearing a sense of musical logic. It is this ability that allows you to intuitively embrace the future work as a single whole and to observe harmony and proportions, obeying the laws of beauty. Through a logical search of options under the control of aesthetic taste, the author weaves a musical canvas from his idea. It is no accident that Henri Poincare, the greatest French philosopher and mathematician, considered the ability to choose the best, most useful combination of creative will as evidence of giftedness.

The right hemisphere of the brain evaluates the whole concept of the musical idea and the left hemisphere decomposes it into sounds. A good ‘architectonic’ hearing is when both hemispheres work in full harmony, but this is rare.

In the experiment of Finite and Carnot, young musicians, students of the University of California, listened to nine versions of the first part of Mozart’s Fortieth Symphony (G minor). In eight versions, the organisers changed the musical fragments and only one corresponded to the original. Alas, no one heard that the faultless logic of the great Austrian was barbarously violated. Moreover, some of the flip-flops deserved more appreciation than the original masterpiece.

Heart sings

Heart sings

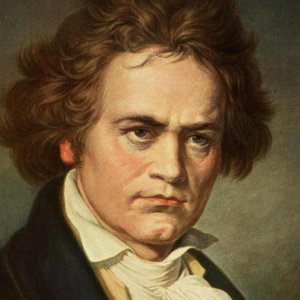

Deafness did not prevent one of the greatest composers of mankind, Ludwig van Beethoven, from creating brilliant works. Still, here’s an interesting point – scientists found that the rhythm of the work could have been a mirror image of the picture of the cardiac contractions of the composer. The analysis was subjected to four significant works, written by Beethoven, when he was absolutely deaf. All of them are characterised by dotted nervousness, unbalanced rhythm and an unexpected arrangement of pauses, reminiscent of the symptoms of arrhythmia.

The silence of the surrounding world left the master alone with his imagination, inner “architectonic” hearing and music of his own heart. All that was created by the composer in the last ten years of his life, he lost in his brilliant head.

The Mozart Effect

Listening to Mozart, people raise their IQ – surely you’ve heard something about it. Go to a search engine, type in the ‘Mozart effect’ and find a lot of suggestions to make you almost a genius. CDs, educational videos and books seem convincing, but when it comes to scientific evidence, the picture seems less unambiguous.

The results of Dr. Gordon Shaw‘s research, published in the journal Nature (1993), literally blew up the social brain. Shaw explored the ability of people to spatially reason, as we tend to do in solving mathematical problems, playing chess or during scientific challenges. Shaw and his assistant created a visual model of the brain and the points of activity were denoted by musical notation – a spontaneously composed musical phrase resembling a classical melody.

The continuation of the story was an experiment to assess the influence of classics on intelligence. As a result of regular listening to the ‘Sonata for two pianofortes in D major’, IQ in the control group of college students rose 9 points above the previous level.

Conclusions made by Shaw provoked a real flurry of similar studies. The results of some confirmed an unprecedented increase in mental abilities, while others, on the contrary, cast doubt on the discovery.

Amazingly, the Governor of the State of Georgia, Zell Miller insisted on the allocation of money from the state budget for the purchase of a new CD for each newborn, with the works of the great Austrian. In the maelstrom of universal excitement, not only babies were affected, as recalled by the professor of neuropsychology of Edinburgh University, Sergio Della Sala. The owner of a dairy in Italy proudly told him that his buffaloes listen to Mozart three times a day and, thus, give the best milk for mozzarella.

Whatever it was, one thing is for certain – from the impact of Mozart‘s music, the intellect certainly will not suffer.

Music from childhood is good

There is a more reliable way to increase IQ with music. However, the effort will be taken more seriously than listening to a CD. Mastering the piano, violin or any other musical instruments positively affects mental development.

Nina Kraus, in an experiment based in the Neuroscience Laboratory of Northwestern University of Illinois, found that early exposure to music not only develops creativity and improves hearing, but also reduces the risk of developing age-related pathologies like Alzheimer’s and senile amnesia.

A group of subjects listened to a sound sequence from scraps of words. Participants, who, in their childhood, completed 4-5 grades of music school, reacted to it faster, despite the admixture of artificial interference. Elderly people with difficulties perceived the often changing fragments, as well. Finally, musically savvy people more accurately picked up changes by ear and by memorised melodies, as they felt their emotional colouring as being more subtle.

Another survey (involving 130 American high school students) showed that musical-rhythmic abilities are a help in learning foreign languages. A developed sense of rhythm activates the neural blocks of speech coding, responsible for the writing-voice communication and language memory. The researchers suggest that the connection between reading and the sense of rhythm arises in the child’s auditory system.

The more we listen, the more we depend on it

Well, what are we all about Mozart – what about modern music? The next generation’s favourite genre – heavy rock – emerged from the belly of the hippie subculture. The attempt to see the world through the narrowness of narrative impressions is also an aesthetic experience, and although the brain is a stress-resistant system, we must not abuse it, testing it for strength. Unfortunately, science does not have anything to say on this subject.

In Soviet Russia, for the sake of experiment, scientists turned to elite schools in Moscow. They arranged a ten-minute disco for high school students, including all the popular rock songs. After the short concert, the students were asked to answer three basic questions on which psychiatrists would determine their adequacy. They were required to give their own name, location and current year. Alas, none of the participants could completely cope with the task.

The number of studies of the damaging factors and their impact on consciousness is enormous and continues to grow, opening up new ‘surprises’. Rigid rhythm, bomb strikes of low frequencies, monotonous repeatability, enchanting light effects, dissolute behaviour of performers and satanic rituals – this mixture is like a drug. Overdosing leads to a psychological stupor and degradation, which is capable of triggering suicide. Something like this happens after taking a lethal dose of heavy drugs. Here is a neuro-aesthetic!

At last

It is fair to say that the cognitive neurobiology of music is experiencing considerable pressure. The objectivity of the conclusions is questioned because of, according to critics, the imperfections and limitations of the methods used. Still, in spite of everything, the research on the influence of music on intellect continues. Recently, emphasis has been placed on non-traditional methods of ‘musical’ therapy for epilepsy, autism and Alzheimer’s disease. The effect of Mozart has not calmed down disputes around the theme of children’s musical development. Scientists are discussing, experimenting, searching, using new technologies to discover and studying neural circuits of the brain. We still have to wait for the results.

Take the children to the opera, the philharmonic society or the ballet. Listen to good music. It is worth it!

“Three sketches of Lucian Freud” by Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon was an English expressionist painter and a master of figurative painting. His triptych, in 2013, became the most expensive work of art in the world. “Three sketches of Lucian Freud” was sold at Christie’s auction for a record sum of 142 million dollars.

The triptych, created by the artist in 1969, was auctioned for the first time at a pre-sale estimate of 85 million dollars. Bidding lasted only six minutes and the auction house did not disclose the identity of the buyer. Each part of the triptych has the same size of 198×147.5 cm. Each canvas depicts Lucien Freud in different poses, while seated on a chair is the artist Lucien Freud. The background is orange-brown, which is brighter than normal for the works of Bacon.

“Number 5” by Jackson Pollock

“Number 5” was completed in 1948 and utilised the technique of spraying, which is the corporate style of the artist. The picture size is 243.8×121.9 cm and is mounted on fibreboard (hardboard).

In 2006, at an auction organised by the auction house Sotheby’s, it was sold for 140 million dollars. It is believed that the hype surrounding this painting was created artificially. All of the paintings of Jackson Pollock were presented in museums and sold freely. Yet, “Number 5” was hidden and shown only when all of the other artworks were sold.

Consequently, the price of the painting went up to the heavens and broke many records. The original painting was in a private collection and was then exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It then became the property of producer David Geffen. Who sold it for $ 140 million? According to unconfirmed reports, it was a famous Mexican billionaire.